Monday, December 25, 2006

Angels

Any ideas why our culture, and ones that have gone before, have portrayed angels as babies, cherubs, or little children? Is that the best we can do when thinking about purity and innocence, or is there something more? Would we like to ignore the Scriptural picture of the terror-striking angels of Isaiah's writing or the flaming sword of the cherubim that guarded in every direction? Just curious. -N.M.

Thursday, November 23, 2006

Thursday, October 05, 2006

Purgatory? Is there an Anglican position?

A cross posting from Father Derrick Hassert. In response to a question in today's high school Bible class.

XXII. Of Purgatory.The Romish Doctrine concerning Purgatory. . .is a fond thing, vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture, but rather repugnant to the Word of God.

Often, when in debate or discussion with other Christians, it is posited that Anglicans believe in “Purgatory.” I often reply “Why do you think that?” The answer usually is “Because you pray for the dead.” Indeed, we do pray for the dead, and we believe the dead pray for and with us—but does this mean that we follow the peculiar teaching of the Church of Rome on this matter? The answer is, based on historical and dogmatic theology, an emphatic “no,” but one that often demands explanation to both Anglicans and those outside of the Anglican tradition.

The equation of Purgatory with the Intermediate State (in the Anglican teaching, the state in which the souls of all of the faithful departed exist before the Resurrection of the dead) is an erroneous one, especially since the Roman Church elaborates upon both Purgatory and the Intermediate State (in this line of thinking, occupied when “the souls” pass out of Purgatory before the Resurrection, translating their status from that of mere “souls” into true “saints,” and thus necessitating the feast day of All Souls along with that of All Saints); to adopt the Roman terms while attempting an Anglican description usually results in linguistic confusion and theological consternation (See Bishop N.T. Wright’s For All the Saints ). Indeed, in that the Roman teaching is clearly rejected in the East, such a teaching can in no wise be held as a “Catholic” doctrine proper. When we read Eastern Orthodox texts on such issues there are often narrow variances of opinion than those found in the West and far less elaboration. This from Father Pomazansky’s Orthodox Dogmatic Theology:

"Concerning the state of the soul after the Particular Judgment, the Orthodox Church teaches thus: “We believe that the souls of the dead are in a state of blessedness or torment according to their deeds. After being separated from the body, they immediately pass over either to joy or into sorrow and grief, however, they do not feel either complete blessedness or complete torment. For complete blessedness or complete torment each one receives after the General Resurrection, when the soul is reunited with the body in which it lived in virtue or in vice (The Epistle of the Eastern Patriarchs on the Orthodox Faith, paragraph 18). Thus the Orthodox Church distinguishes two different conditions after the Particular Judgment: one for the righteous, another for sinners; in other words, paradise and hell. The Church does not recognize the Roman Catholic teaching of three conditions: 1) blessedness, 2) purgatory, and 3) gehenna (hell). The very name “gehenna” the Fathers of the Church usually refer to the condition after the Last judgment, when both death and hell will be cast into the “lake of fire” (Rev. 20:15)."

Here it would seem difficult to apply the “Purgatory” label as many moderns wish to use it. When we look at other Anglican dogmatic texts, such as Browne’s Exposition on the Thirty-Nine Articles, or The Christian Faith by C.B. Moss we are confronted with differing views on these issues within a narrow range of opinion, seeming closer to the Orthodox teaching than to the Roman.

Few Anglican authors and even fewer Orthodox authors use the term or designation “Intermediate State” to denote a place of pain, suffering, or retribution for sin. However, the Roman Catholic tradition, and some Anglo-Catholics modeling their views after it, emphasizes the pain and satisfaction that are required of the sinner for the sins of his life. How are we to keep this line of thinking in concert with the Comfortable Words (all from the Holy Scriptures) of the Anglican Eucharist, in which we are assured from Scripture that Christ is the propitiation for our sins? Indeed, how are we to read such a view of purgation (in which a satisfaction of pain is required) in light of the Anglican Eucharist’s canon that states Christ is the “full, perfect, and sufficient sacrifice, oblation, and satisfaction, for the sins of the whole world”? N.T Wright summarizes the issue when he says in For All the Saints:

"I cannot stress sufficiently that if we raise the question of punishment for sin, this is something that has already been dealt with on the cross of Jesus. Of course, there have been crude and unbiblical versions of the doctrine of the atonement, and many have rightly reacted against the idea of a vengeful God determined to punish someone and being satisfied by taking it out on his own son. But this is to mistake caricature for biblical doctrine. Paul says, in his most central and careful statement, not that God punished Jesus, but that God 'condemned sin in the flesh' of Jesus (Romans 8.3). Here the instincts of the Reformers, if not always their exact expressions, were spot on. The idea that Christians need to suffer punishment for their sins in a post-mortem purgatory, or anywhere else, reveals a straightforward failure to grasp the very heart of what was achieved on the cross." p 30

We should view any period of “purgation” (if we are even to employ the term, perhaps “growth” or “purification” would be better terms) in the Intermediate State as the 1549 English and 1928 American Prayer Books put it; as simply a period of “continual growth” in God’s “love and service,” a view I have heard espoused by Lutherans, Anglicans, Orthodox, and Baptists alike (a Baptist New Testament professor of mine from Westminster Seminary described it in this manner). This way of thinking of the Intermediate State puts to rest notions of satisfaction for sin and places the emphasis on the inexhaustible nature and love of God; it also eliminates any notion of the ahistorical and theologically incoherent idea of an “Anglican doctrine of Purgatory.”

I include the Eastern Orthodox position to show that the notion of Purgatory as found in Roman teachings is not found in the East, and therefore cannot as such be labeled as “Catholic,” unless we take the Roman doctrine to be the measure of the terminology. Indeed, the classical Anglican position on prayers for the departed bears a greater resemblance to Orthodoxy than it does to the medieval concepts of the Church of Rome. As Meyendorff (1979) recounts in Byzantine Theology:

"The debate between Greeks and Latins (on the question of Purgatory). . . showed a radical difference in perspective. While the Latins took for granted their legalistic approach to divine justice—which, according to them, requires a retribution for every sinful act—the Greeks interpreted sin less in terms of the acts committed than in terms of a moral and spiritual disease which was to be healed by divine forbearance and love. The Latins also emphasized the idea of an individual judgment by God of each soul, a judgment which distributes the souls in three categories: the just, the wicked, and those in a middle category—who need to be “purified” by fire. The Greeks, meanwhile, without denying a particular judgment after death or agreeing on the existence of the three categories, maintained that neither the just nor the wicked will attain their final state of either bliss or condemnation before the last day. Both sides agreed that prayers for the departed are necessary and helpful. . .even the just need them;. . .in particular. . .the Eucharistic canon of Chrysostom’s liturgy. . .offers the “bloodless sacrifice” for “patriarchs, prophets, apostles, and every righteous spirit made perfect in faith,” even for the Virgin Mary herself." p 220-221

So here even the state of the most blessed is to be viewed

". . .not as a legal and static justification, but as a never-ending ascent, into which the entire communion of saints—the Church in heaven and the Church on earth—has been initiated in Christ. In the communion of the Body of Christ, all members of the Church, living or dead, are interdependent and united by ties of love and mutual concern; thus the prayers of the Church on earth and the intercession of the saints in heaven can effectively help all sinners, i.e., all men, to get closer to God." p 221

This view of growth during the Intermediate State as a “never-ending ascent” is expressed, as was mentioned above, in the Anglican Eucharists of the 1549 English and 1928 American Prayer Books. The emphasis is not on penance, nor on pain, nor satisfaction for sins (which Christ has already paid) but on growth “in the knowledge and the love of God” of those who have “died in thy faith and fear.” This emphasis is the Body of Christ as the Communion of Saints, who all continue in their walk with God before the Resurrection, is taught in the American Prayer Book—but it goes no further than this measured theology and it is accepted by and differentiated from Purgatory by Reformed minded Anglicans. Litton’s Introduction to Dogmatic Theology, a text that places Anglican theology firmly in the Reformed (Calvinist) school of thought, summarizes the difference between the Roman concept of Purgatory and the traditional doctrine of the Intermediate State shared by most Christians not in the Roman Communion (notice the similarity to Meyendorff’s logic):

"The Romish doctrine of purgatory must not be confounded with the belief of spiritual progress in the intermediate state, against which no objection from reason or Scripture can be urged. . . .But the doctrine of the Roman schools is of a different character. It is forensic in nature, and implies the payment of debt not fully discharged in this life. "

As noted above, in Orthodox theology, the prayers for the faithful departed are even offered for the Virgin Mary (assuming that she too is increasing in grace and the knowledge and presence of God and being conformed to His image—theosis). Therefore, praying for the faithful departed—as expressed in the 1928 American Prayer Book—is a truly “Catholic” doctrine and can be held by Anglicans, as is praying with them in the worship of the Church: “Therefore with Angels and Archangels and with all the company of heaven, we laud and magnify thy glorious Name. . .” We pray for the faithful departed in their growth in love and knowledge of God’s love as well as with them in the thanksgiving of the Sacrament of Christ’s Body and Blood.

XXII. Of Purgatory.The Romish Doctrine concerning Purgatory. . .is a fond thing, vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture, but rather repugnant to the Word of God.

Often, when in debate or discussion with other Christians, it is posited that Anglicans believe in “Purgatory.” I often reply “Why do you think that?” The answer usually is “Because you pray for the dead.” Indeed, we do pray for the dead, and we believe the dead pray for and with us—but does this mean that we follow the peculiar teaching of the Church of Rome on this matter? The answer is, based on historical and dogmatic theology, an emphatic “no,” but one that often demands explanation to both Anglicans and those outside of the Anglican tradition.

The equation of Purgatory with the Intermediate State (in the Anglican teaching, the state in which the souls of all of the faithful departed exist before the Resurrection of the dead) is an erroneous one, especially since the Roman Church elaborates upon both Purgatory and the Intermediate State (in this line of thinking, occupied when “the souls” pass out of Purgatory before the Resurrection, translating their status from that of mere “souls” into true “saints,” and thus necessitating the feast day of All Souls along with that of All Saints); to adopt the Roman terms while attempting an Anglican description usually results in linguistic confusion and theological consternation (See Bishop N.T. Wright’s For All the Saints ). Indeed, in that the Roman teaching is clearly rejected in the East, such a teaching can in no wise be held as a “Catholic” doctrine proper. When we read Eastern Orthodox texts on such issues there are often narrow variances of opinion than those found in the West and far less elaboration. This from Father Pomazansky’s Orthodox Dogmatic Theology:

"Concerning the state of the soul after the Particular Judgment, the Orthodox Church teaches thus: “We believe that the souls of the dead are in a state of blessedness or torment according to their deeds. After being separated from the body, they immediately pass over either to joy or into sorrow and grief, however, they do not feel either complete blessedness or complete torment. For complete blessedness or complete torment each one receives after the General Resurrection, when the soul is reunited with the body in which it lived in virtue or in vice (The Epistle of the Eastern Patriarchs on the Orthodox Faith, paragraph 18). Thus the Orthodox Church distinguishes two different conditions after the Particular Judgment: one for the righteous, another for sinners; in other words, paradise and hell. The Church does not recognize the Roman Catholic teaching of three conditions: 1) blessedness, 2) purgatory, and 3) gehenna (hell). The very name “gehenna” the Fathers of the Church usually refer to the condition after the Last judgment, when both death and hell will be cast into the “lake of fire” (Rev. 20:15)."

Here it would seem difficult to apply the “Purgatory” label as many moderns wish to use it. When we look at other Anglican dogmatic texts, such as Browne’s Exposition on the Thirty-Nine Articles, or The Christian Faith by C.B. Moss we are confronted with differing views on these issues within a narrow range of opinion, seeming closer to the Orthodox teaching than to the Roman.

Few Anglican authors and even fewer Orthodox authors use the term or designation “Intermediate State” to denote a place of pain, suffering, or retribution for sin. However, the Roman Catholic tradition, and some Anglo-Catholics modeling their views after it, emphasizes the pain and satisfaction that are required of the sinner for the sins of his life. How are we to keep this line of thinking in concert with the Comfortable Words (all from the Holy Scriptures) of the Anglican Eucharist, in which we are assured from Scripture that Christ is the propitiation for our sins? Indeed, how are we to read such a view of purgation (in which a satisfaction of pain is required) in light of the Anglican Eucharist’s canon that states Christ is the “full, perfect, and sufficient sacrifice, oblation, and satisfaction, for the sins of the whole world”? N.T Wright summarizes the issue when he says in For All the Saints:

"I cannot stress sufficiently that if we raise the question of punishment for sin, this is something that has already been dealt with on the cross of Jesus. Of course, there have been crude and unbiblical versions of the doctrine of the atonement, and many have rightly reacted against the idea of a vengeful God determined to punish someone and being satisfied by taking it out on his own son. But this is to mistake caricature for biblical doctrine. Paul says, in his most central and careful statement, not that God punished Jesus, but that God 'condemned sin in the flesh' of Jesus (Romans 8.3). Here the instincts of the Reformers, if not always their exact expressions, were spot on. The idea that Christians need to suffer punishment for their sins in a post-mortem purgatory, or anywhere else, reveals a straightforward failure to grasp the very heart of what was achieved on the cross." p 30

We should view any period of “purgation” (if we are even to employ the term, perhaps “growth” or “purification” would be better terms) in the Intermediate State as the 1549 English and 1928 American Prayer Books put it; as simply a period of “continual growth” in God’s “love and service,” a view I have heard espoused by Lutherans, Anglicans, Orthodox, and Baptists alike (a Baptist New Testament professor of mine from Westminster Seminary described it in this manner). This way of thinking of the Intermediate State puts to rest notions of satisfaction for sin and places the emphasis on the inexhaustible nature and love of God; it also eliminates any notion of the ahistorical and theologically incoherent idea of an “Anglican doctrine of Purgatory.”

I include the Eastern Orthodox position to show that the notion of Purgatory as found in Roman teachings is not found in the East, and therefore cannot as such be labeled as “Catholic,” unless we take the Roman doctrine to be the measure of the terminology. Indeed, the classical Anglican position on prayers for the departed bears a greater resemblance to Orthodoxy than it does to the medieval concepts of the Church of Rome. As Meyendorff (1979) recounts in Byzantine Theology:

"The debate between Greeks and Latins (on the question of Purgatory). . . showed a radical difference in perspective. While the Latins took for granted their legalistic approach to divine justice—which, according to them, requires a retribution for every sinful act—the Greeks interpreted sin less in terms of the acts committed than in terms of a moral and spiritual disease which was to be healed by divine forbearance and love. The Latins also emphasized the idea of an individual judgment by God of each soul, a judgment which distributes the souls in three categories: the just, the wicked, and those in a middle category—who need to be “purified” by fire. The Greeks, meanwhile, without denying a particular judgment after death or agreeing on the existence of the three categories, maintained that neither the just nor the wicked will attain their final state of either bliss or condemnation before the last day. Both sides agreed that prayers for the departed are necessary and helpful. . .even the just need them;. . .in particular. . .the Eucharistic canon of Chrysostom’s liturgy. . .offers the “bloodless sacrifice” for “patriarchs, prophets, apostles, and every righteous spirit made perfect in faith,” even for the Virgin Mary herself." p 220-221

So here even the state of the most blessed is to be viewed

". . .not as a legal and static justification, but as a never-ending ascent, into which the entire communion of saints—the Church in heaven and the Church on earth—has been initiated in Christ. In the communion of the Body of Christ, all members of the Church, living or dead, are interdependent and united by ties of love and mutual concern; thus the prayers of the Church on earth and the intercession of the saints in heaven can effectively help all sinners, i.e., all men, to get closer to God." p 221

This view of growth during the Intermediate State as a “never-ending ascent” is expressed, as was mentioned above, in the Anglican Eucharists of the 1549 English and 1928 American Prayer Books. The emphasis is not on penance, nor on pain, nor satisfaction for sins (which Christ has already paid) but on growth “in the knowledge and the love of God” of those who have “died in thy faith and fear.” This emphasis is the Body of Christ as the Communion of Saints, who all continue in their walk with God before the Resurrection, is taught in the American Prayer Book—but it goes no further than this measured theology and it is accepted by and differentiated from Purgatory by Reformed minded Anglicans. Litton’s Introduction to Dogmatic Theology, a text that places Anglican theology firmly in the Reformed (Calvinist) school of thought, summarizes the difference between the Roman concept of Purgatory and the traditional doctrine of the Intermediate State shared by most Christians not in the Roman Communion (notice the similarity to Meyendorff’s logic):

"The Romish doctrine of purgatory must not be confounded with the belief of spiritual progress in the intermediate state, against which no objection from reason or Scripture can be urged. . . .But the doctrine of the Roman schools is of a different character. It is forensic in nature, and implies the payment of debt not fully discharged in this life. "

As noted above, in Orthodox theology, the prayers for the faithful departed are even offered for the Virgin Mary (assuming that she too is increasing in grace and the knowledge and presence of God and being conformed to His image—theosis). Therefore, praying for the faithful departed—as expressed in the 1928 American Prayer Book—is a truly “Catholic” doctrine and can be held by Anglicans, as is praying with them in the worship of the Church: “Therefore with Angels and Archangels and with all the company of heaven, we laud and magnify thy glorious Name. . .” We pray for the faithful departed in their growth in love and knowledge of God’s love as well as with them in the thanksgiving of the Sacrament of Christ’s Body and Blood.

Thursday, August 31, 2006

Wednesday, July 05, 2006

I was afraid that no one would see these thoughts and questions, as they were buried on an old post. So, Serena, I thought I would post them here and see if we can get some takers....

"I'm reading the Brothers Karamazov right now and [the problem of evil] is certainly one of the chief subjects in the book. How could God allow grief and evil and suffering that is completely non-redemptive? But is there such a thing as non-redemptive suffering? Does 'goodness' necessarily mean that God should stop the above? If not, then how should we understand God? Who is this God person anyway? It makes my head hurt, all the possibilities. Ho hum. Life is very complicated. But then, if it wasn't, it would be very boring. Half the fun of living is learning."

-Serena

"I'm reading the Brothers Karamazov right now and [the problem of evil] is certainly one of the chief subjects in the book. How could God allow grief and evil and suffering that is completely non-redemptive? But is there such a thing as non-redemptive suffering? Does 'goodness' necessarily mean that God should stop the above? If not, then how should we understand God? Who is this God person anyway? It makes my head hurt, all the possibilities. Ho hum. Life is very complicated. But then, if it wasn't, it would be very boring. Half the fun of living is learning."

-Serena

Tuesday, July 04, 2006

St. Andrew's Academy is Hiring

St. Andrew’s Academy is looking for teachers for the 2006-2007 school year. St. Andrew’s is a K-12, Anglican, classically oriented, college preparatory, parochial school in Lake Almanor, California. We are currently looking for individuals who want to make a difference in students’ lives and the culture at large. Our teachers typically work across a variety of grade levels, but one of our most pressing needs is for grammar school instructors—ones that can provide a stable character influence and set an example of excellence for our youngest students.

Successful applicants do not need teaching experience, but will need to learn and apply instruction. If you have teaching experience, we won’t hold this against you too much. Confidence, honesty, and self-motivation will also be key. Because of the classical emphasis, experience in Latin and New Testament Greek are definite benefits.

The Lake Almanor/Lassen National park area is situated at the northernmost end of the Sierra-Nevada Range and at the southernmost end of the Cascade Range. The environment is alpine with pleasant summers and snowy winters, and the natural landscape is quite spectacular. Recreational opportunities such as fishing, hunting, hiking, kayaking, and cross-country and downhill skiing are plentiful, and the local communities are rural. The school is located about 1.5 hours northeast of Chico, California, and 2 hours northwest of Reno, Nevada.

The motto of St. Andrew’s is “Oratio, Studium, Labor,” which translated is “Prayer, Study, Work,” for this reflects our school’s priorities. Everyday begins and ends with traditional sung prayers, and our students know that our worship is the most important part of the day. Of course, our academic expectations of students are demanding, but in the context of the Christian life, this is viewed as an opportunity to glorify God. We also ask the students to take ownership of their school by helping to maintain the facilities and to work in other ways to serve their neighbors. Involvement at St. Andrew’s is not separable from community life; we constantly seek to encourage and build our community. This is specially important for the faculty as they often lead in this task. As a group of colleagues, we seek to pursue Truth, Goodness, and Beauty, and daily invite our students to join us. This is our educational task. Being involved with St. Andrew’s is rarely easy, but always adventurous and rewarding.

Applicants must understand that St. Andrew’s has always been a work of faith, and as such, there is some risk involved. This is therefore a step of faith for all our staff, but please understand that God has always met our needs—and the needs of our faculty—and the ethos of the school would not be the same without constant dependence on Him.

If this mission intrigues you, please give us a call at 530-596-3343 and ask to speak to Father Brian Foos, Headmaster, or Mr. Kent Bartel, Assistant Headmaster, or drop us an email at. If you have a chance, please email your Curriculum Vitae (academic resume) to the same address.

Successful applicants do not need teaching experience, but will need to learn and apply instruction. If you have teaching experience, we won’t hold this against you too much. Confidence, honesty, and self-motivation will also be key. Because of the classical emphasis, experience in Latin and New Testament Greek are definite benefits.

The Lake Almanor/Lassen National park area is situated at the northernmost end of the Sierra-Nevada Range and at the southernmost end of the Cascade Range. The environment is alpine with pleasant summers and snowy winters, and the natural landscape is quite spectacular. Recreational opportunities such as fishing, hunting, hiking, kayaking, and cross-country and downhill skiing are plentiful, and the local communities are rural. The school is located about 1.5 hours northeast of Chico, California, and 2 hours northwest of Reno, Nevada.

The motto of St. Andrew’s is “Oratio, Studium, Labor,” which translated is “Prayer, Study, Work,” for this reflects our school’s priorities. Everyday begins and ends with traditional sung prayers, and our students know that our worship is the most important part of the day. Of course, our academic expectations of students are demanding, but in the context of the Christian life, this is viewed as an opportunity to glorify God. We also ask the students to take ownership of their school by helping to maintain the facilities and to work in other ways to serve their neighbors. Involvement at St. Andrew’s is not separable from community life; we constantly seek to encourage and build our community. This is specially important for the faculty as they often lead in this task. As a group of colleagues, we seek to pursue Truth, Goodness, and Beauty, and daily invite our students to join us. This is our educational task. Being involved with St. Andrew’s is rarely easy, but always adventurous and rewarding.

Applicants must understand that St. Andrew’s has always been a work of faith, and as such, there is some risk involved. This is therefore a step of faith for all our staff, but please understand that God has always met our needs—and the needs of our faculty—and the ethos of the school would not be the same without constant dependence on Him.

If this mission intrigues you, please give us a call at 530-596-3343 and ask to speak to Father Brian Foos, Headmaster, or Mr. Kent Bartel, Assistant Headmaster, or drop us an email at

Sunday, May 28, 2006

St. Andrew's 2006 Drama Production

This year we did two short plays rather than a single long one.

Our first play was "The Coming of Gowf," a comedy based on the story by P.G. Wodehouse, about a melancholy king who discovers a new religion: Gowf. It cheers him up mightily, and when his bride-to-be confesses she also is a worshiper of the great Gowf, they (naturally) live happily ever after.

How shall we cheer up the King?

The King discovers Gowf.

Princess, your slave!

The cast of "The Coming of Gowf"

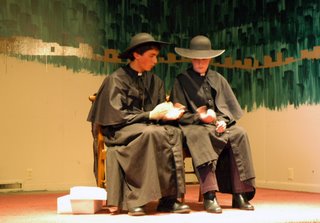

Our second play was "The Blue Cross," adapted from G. K. Chesterton's story of the same name. It is a detective mystery, in which the famous Valentina follows mysterious clues all over London, to find what seem to be merely two harmless clergymen, sitting in a park. But as it turns out, neither one is exactly as he seems.

Flambeau's in England! They don't call him a master of disguises for no reason.

Ah, but Valentina's coming soon.

Just two clergymen in the park.

Or are they?

Caught!

The Cast

Our first play was "The Coming of Gowf," a comedy based on the story by P.G. Wodehouse, about a melancholy king who discovers a new religion: Gowf. It cheers him up mightily, and when his bride-to-be confesses she also is a worshiper of the great Gowf, they (naturally) live happily ever after.

How shall we cheer up the King?

The King discovers Gowf.

Princess, your slave!

The cast of "The Coming of Gowf"

Our second play was "The Blue Cross," adapted from G. K. Chesterton's story of the same name. It is a detective mystery, in which the famous Valentina follows mysterious clues all over London, to find what seem to be merely two harmless clergymen, sitting in a park. But as it turns out, neither one is exactly as he seems.

Flambeau's in England! They don't call him a master of disguises for no reason.

Ah, but Valentina's coming soon.

Just two clergymen in the park.

Or are they?

Caught!

The Cast

Wednesday, April 05, 2006

Thursday, March 23, 2006

OUR SAN FRANCISCO 2006 TRIP

One of the great blessings of this year's cultural trip (and there were many) was attending worship, and leading it a few times, in churches where we don't normally get to worship. The most different from our normal venue was a Russian Orthodox Cathedral, which took place half in English, half in Church Slovanic, and lasted an hour and one half. Did I mention that the Orthodox stand for their whole service? Except when they are prostrating themselves on the ground, that is. Even though I felt like I knew a bit more what heaven would be like --continually praising God in a setting completely not like mundane life -- I certainly was thankful for Thomas Cranmer and his wise "trimming" of the services so that congregations could also participate. For, as beautiful this Orthodox service was in its own way (a certain faculty member might disagree here!), it was anything but participator-friendly. And I don't think they mean for it to be especially participator-friendly. I mentioned its length already. They also spoke remarkably quickly, and had no time factored in for congregational responses. I suppose either of these being changed would lead to a service twice as long (this was vespers, compline and mattins all in one -- eep!). People walked around the back of the... nave?.. during the whole liturgy, offering their own private prayers, a few pausing for a while to hear the service, between where we the congregation sat and the choir area. Then, of course, the entire chancel area was blocked off from congregants, with no altar visible. Aside from the theology of it, I found this set up to be visually disorienting, giving no place for the eye to rest.

I supposed I would get used to it if I had need to, and I still think I have more in common theologically with the East than with Rome. But it would really be a loss to do away wtih congregational participation, and a service in a known language, since in this service at least, they spoke so quickly that even the English I could pick out didn't qualify as a known tongue to me except about two words out of ten.

But the music was amazing. Haunting and eastern, to western ears, but with resolution and some measure of tonic rest at the conclusion of the phrases which (I think) we don't find in other eastern music. The heightened tension, if I can speak as one with little music training, seemed to show how far above us God is, and then the resolution at the end said, "You can still come near." I'd like to hear that again.

And of course, never forget the hats of the Orthodox bishops, which only sort of conceal the long ponytails that go with their long beards. We met a very gracious bishop from the Orthodox Church of America, the Bishop of Berkeley, Bishop Benjamin, who showed us around Holy Trinity Cathedral for as long as he could until he had to leave to do a funeral. We appreciated it very much.

Wednesday, March 15, 2006

Saint Patrick's Breastplate

(For those who are always requesting hymn 268)

Fáed Fíada - The Cry of the Deer

I arise today through a mighty strength, the invocation of the

Trinity, through belief in the Threeness, through confession

of the Oneness of the Creator of creation.

I arise today through the strength of Christ with His Baptism,

through the strength of His Crucifixion with His Burial

through the strength of His Resurrection with His Ascension,

through the strength of His descent for the Judgment of Doom.

I arise today through the strength of the love of Cherubim

in obedience of Angels, in the service of the Archangels,

in hope of resurrection to meet with reward,

in prayers of Patriarchs, in predictions of Prophets,

in preachings of Apostles, in faiths of Confessors,

in innocence of Holy Virgins, in deeds of righteous men.

I arise today, through the strength of Heaven:

light of Sun, brilliance of Moon, splendour of Fire,

speed of Lightning, swiftness of Wind, depth of Sea,

stability of Earth, firmness of Rock.

I arise today, through God's strength to pilot me:

God's might to uphold me, God's wisdom to guide me,

God's eye to look before me, God's ear to hear me,

God's word to speak for me, God's hand to guard me,

God's way to lie before me, God's shield to protect me,

God's host to secure me:

against snares of devils, against temptations of vices,

against inclinations of nature, against everyone who

shall wish me ill, afar and anear, alone and in a crowd.

I summon today all these powers between me (and these evils):

against every cruel and merciless power that may oppose

my body and my soul,

against incantations of false prophets,

against black laws of heathenry,

against false laws of heretics, against craft of idolatry,

against spells of witches and smiths and wizards,

against every knowledge that endangers man's body and soul.

Christ to protect me today

against poison, against burning, against drowning,

against wounding, so that there may come abundance of reward.

Christ with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me, Christ in me,

Christ beneath me, Christ above me, Christ on my right,

Christ on my left, Christ in breadth, Christ in length,

Christ in height, Christ in the heart of every man who thinks of me,

Christ in the mouth of every man who speaks of me,

Christ in every eye that sees me, Christ in every ear that hears me.

I arise today through a mighty strength, the invocation of the

Trinity, through belief in the Threeness, through confession of the

Oneness of the Creator of creation.

Salvation is of the Lord. Salvation is of the Lord.

Salvation is of Christ. May Thy Salvation, O Lord, be ever with us.

Fáed Fíada - The Cry of the Deer

I arise today through a mighty strength, the invocation of the

Trinity, through belief in the Threeness, through confession

of the Oneness of the Creator of creation.

I arise today through the strength of Christ with His Baptism,

through the strength of His Crucifixion with His Burial

through the strength of His Resurrection with His Ascension,

through the strength of His descent for the Judgment of Doom.

I arise today through the strength of the love of Cherubim

in obedience of Angels, in the service of the Archangels,

in hope of resurrection to meet with reward,

in prayers of Patriarchs, in predictions of Prophets,

in preachings of Apostles, in faiths of Confessors,

in innocence of Holy Virgins, in deeds of righteous men.

I arise today, through the strength of Heaven:

light of Sun, brilliance of Moon, splendour of Fire,

speed of Lightning, swiftness of Wind, depth of Sea,

stability of Earth, firmness of Rock.

I arise today, through God's strength to pilot me:

God's might to uphold me, God's wisdom to guide me,

God's eye to look before me, God's ear to hear me,

God's word to speak for me, God's hand to guard me,

God's way to lie before me, God's shield to protect me,

God's host to secure me:

against snares of devils, against temptations of vices,

against inclinations of nature, against everyone who

shall wish me ill, afar and anear, alone and in a crowd.

I summon today all these powers between me (and these evils):

against every cruel and merciless power that may oppose

my body and my soul,

against incantations of false prophets,

against black laws of heathenry,

against false laws of heretics, against craft of idolatry,

against spells of witches and smiths and wizards,

against every knowledge that endangers man's body and soul.

Christ to protect me today

against poison, against burning, against drowning,

against wounding, so that there may come abundance of reward.

Christ with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me, Christ in me,

Christ beneath me, Christ above me, Christ on my right,

Christ on my left, Christ in breadth, Christ in length,

Christ in height, Christ in the heart of every man who thinks of me,

Christ in the mouth of every man who speaks of me,

Christ in every eye that sees me, Christ in every ear that hears me.

I arise today through a mighty strength, the invocation of the

Trinity, through belief in the Threeness, through confession of the

Oneness of the Creator of creation.

Salvation is of the Lord. Salvation is of the Lord.

Salvation is of Christ. May Thy Salvation, O Lord, be ever with us.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)